This is Ohlone land

The human history of this land did not begin when colonists arrived. We acknowledge Lafayette Park is located on the un-ceded and occupied territories of the Ramaytush Ohlone. We have a responsibility to acknowledge the history and legacy of colonialism and the privileges gained by it. Please learn, engage, and act for justice.

This page presents a history of how the city of San Francisco established and developed Lafayette Park. It is not the only history of this place, nor the most important.

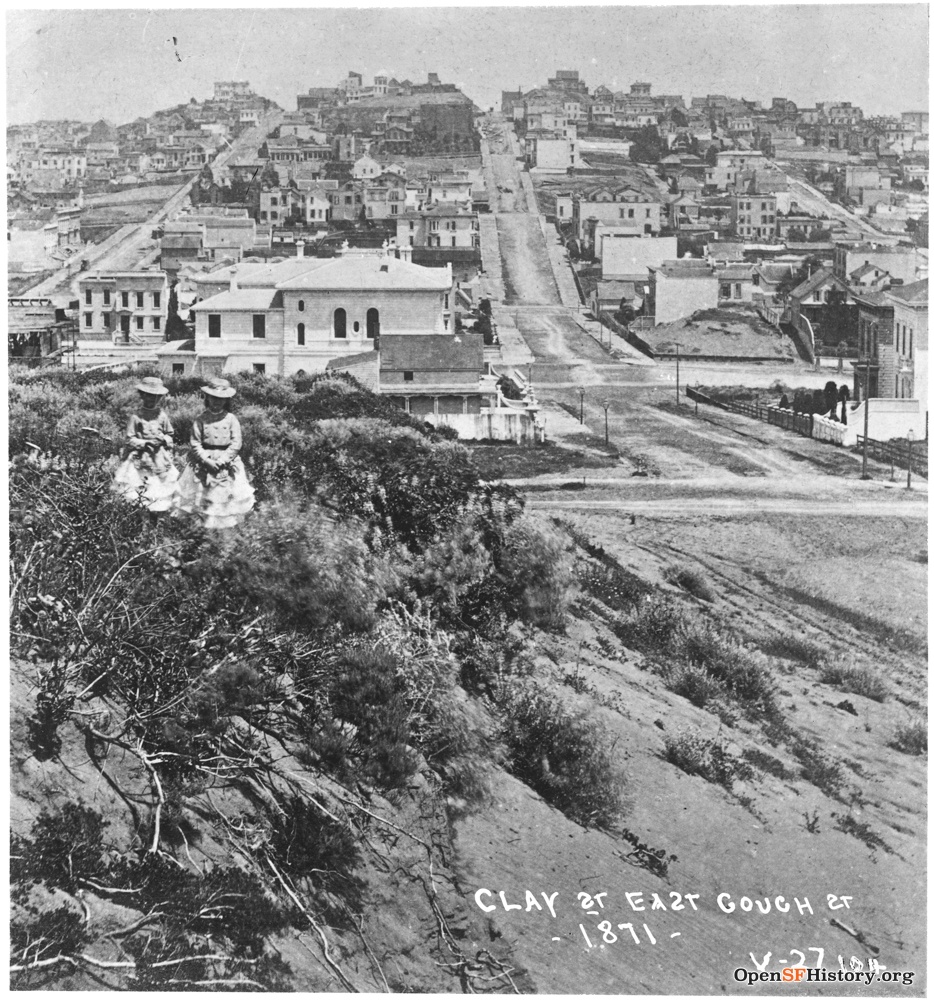

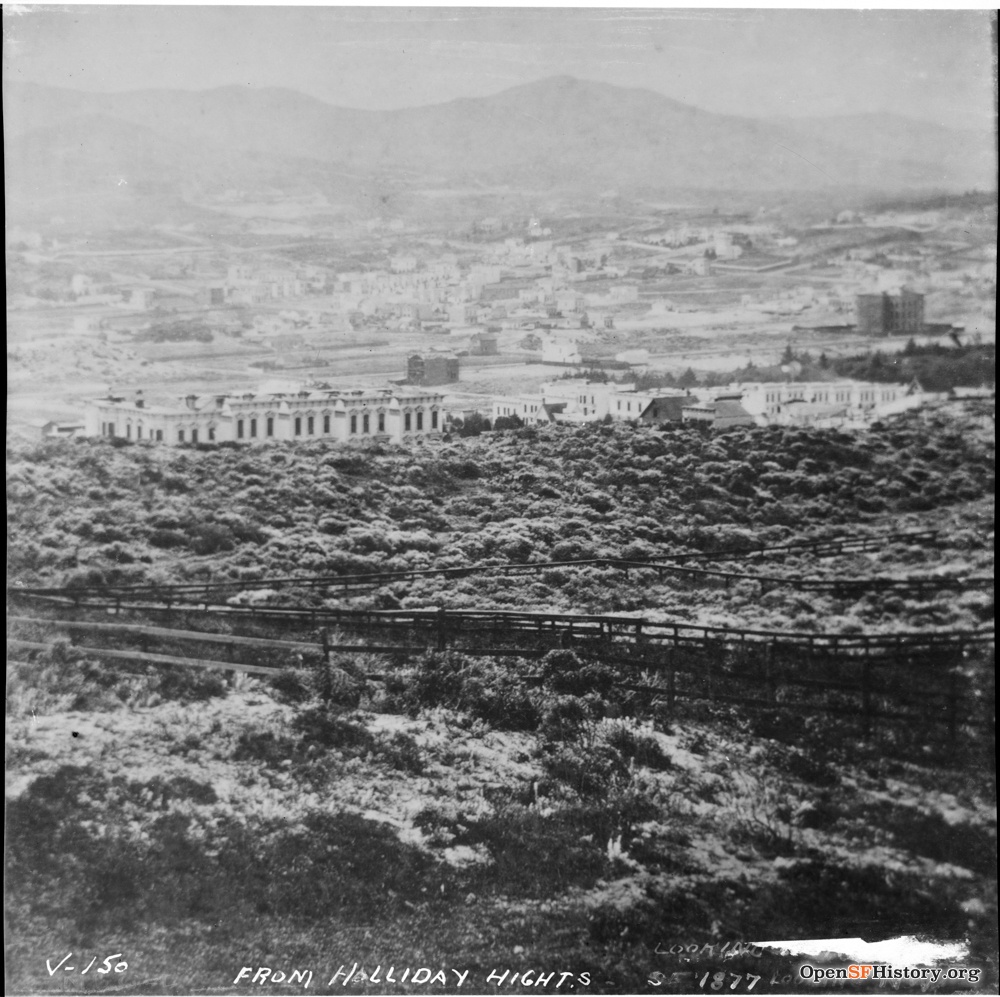

The Earliest Images of Lafayette Park

Holladay Heights vs. Lafayette Park

1858 map showing competing land claims

1895 illustration from The San Francisco Call

The Holladay mansion in 1924, unoccupied by that time. Courtesy Bancroft Library, UC Berkeley

The Van Ness Ordinances of 1856 to 1858 resulted in the annexation and mapping of the Western Addition into San Francisco, including the designation of four blocks to become “Lafayette Square,” named for Marquis de Lafayette, the popular French hero of the American Revolution. City limits previously ended at Larkin Street but now extended to Divisadero.

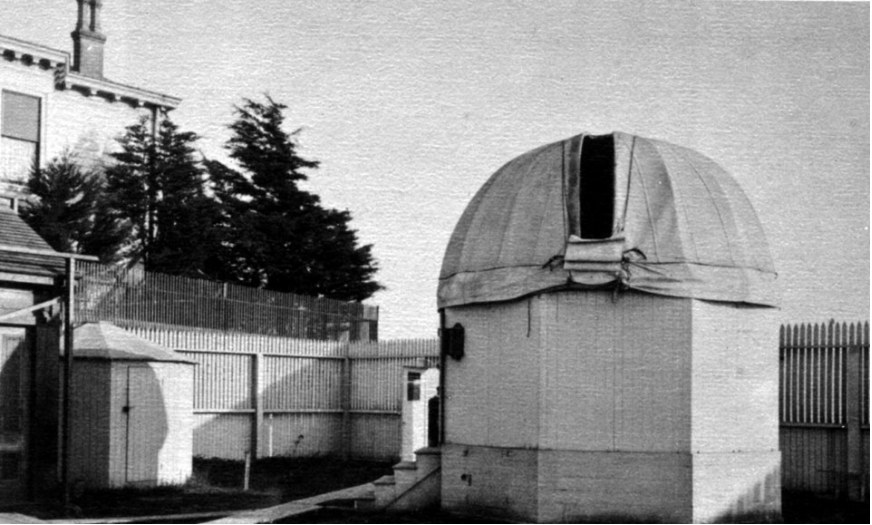

However, Samuel Wirt Holladay (1823-1915), a prominent attorney, challenged the city’s claims to ownership of six parcels of land in what is now eastern Lafayette Park. This legal battle continued for seventy years, mostly in Holladay’s favor. Defending his claim, Holladay fenced in his six parcels along Clay between Gough and Octavia, including the peak of the hill. He built a well, water tower, stable, gardens, and Italianate Victorian mansion, which he occupied from 1870 until the early 1900s. He referred to the estate as Holladay Heights.

Lafayette Park remained little more than an “unimproved sand hill” through the 1890s, despite the formation of the Lafayette Park Improvement Club by neighbors. The City had several other title claims besides Holladay’s to fight before much work on developing the park land could begin. Most of these fights were settled in favor of the City by 1900, but not Holladay’s. The Supreme Court ruled in favor of Holladay in 1896, ending the dispute.

The present design of Lafayette Park, with its formal western half and heavily wooded eastern half, stems directly from this seven-decade dispute.

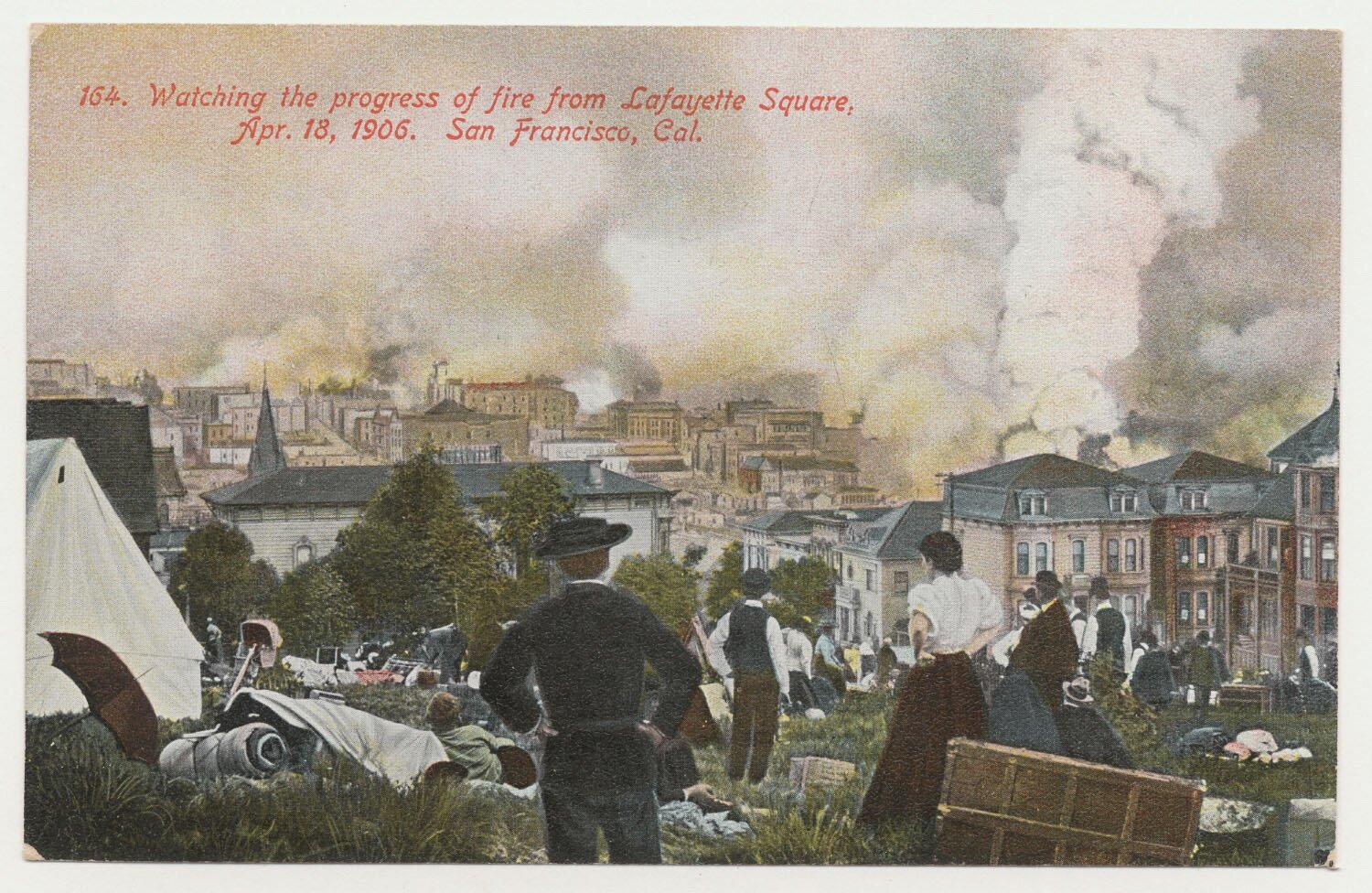

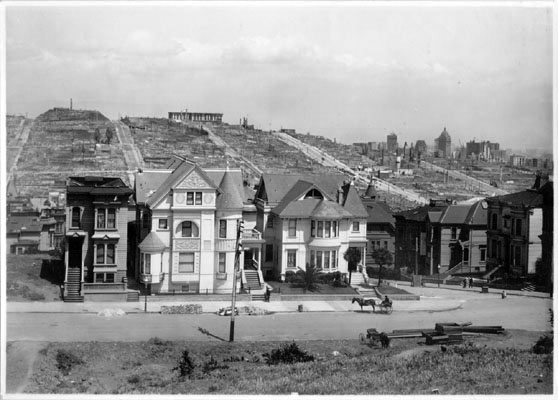

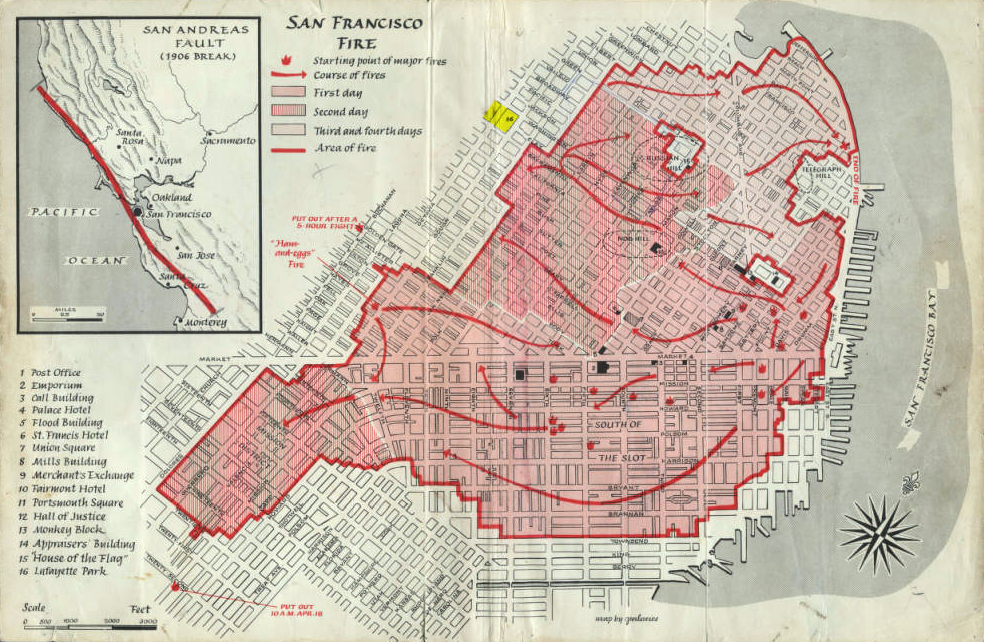

April 18, 1906

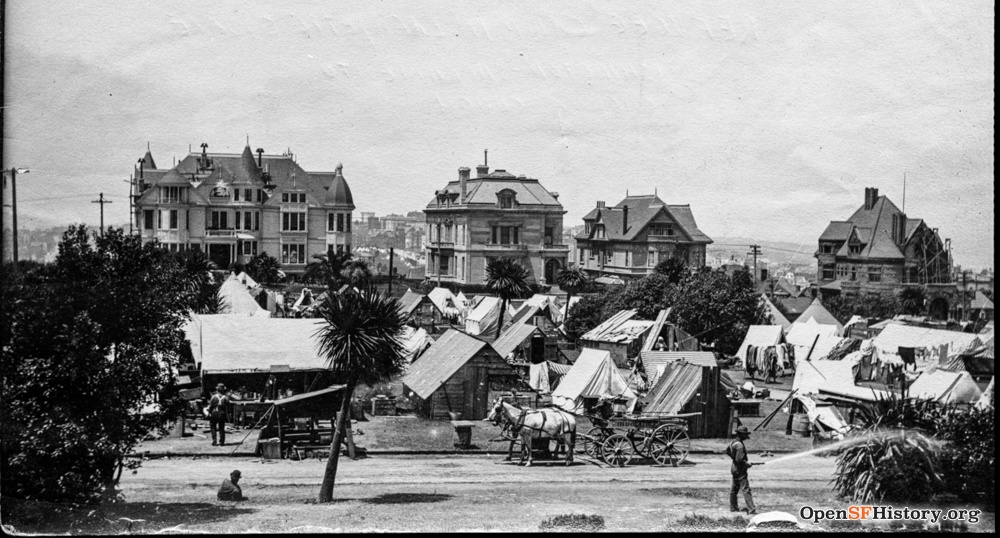

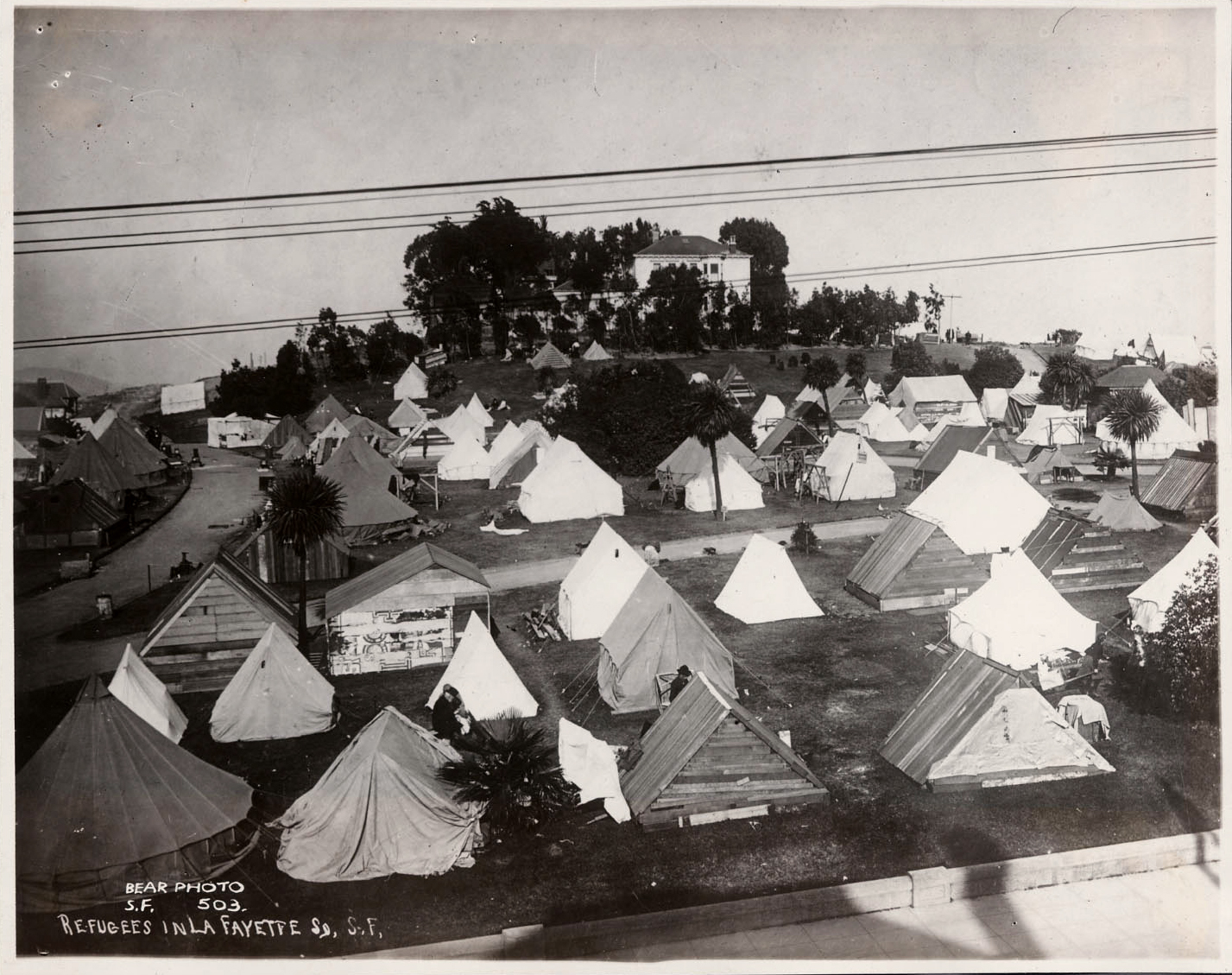

A major earthquake followed by 4 days of fires destroyed 80% of the city’s buildings and left half of San Franciscans homeless. As one of nearest summits outside the fire zone, citizens congregated in Lafayette Park for safety and several iconic photos were taken of the destruction.

Lafayette Park was used as an emergency refugee camp into 1907.

In 1912 the Park Commission funded construction of a “convenience station” (bathroom) at Lafayette Park, and stone sidewalks with granite curbing were constructed in 1913. The Holladay mansion and its gardens remained standing, but grew increasingly eerie as the vacated property deteriorated from neglect.

By 1897, Holladay sold off a parcel of his land fronting Gough Street. Since 1908, the St. Regis Apartment Building, designed by master architect C. A. Muessdorffer, has occupied this site (now 1925 Gough Street). A second house was constructed at the northwest corner of Gough and Clay, where prominent San Francisco resident, and journalist and proprietor of the San Francisco Bulletin, Robert A. Crothers lived from 1918 until about 1930.

The St. Regis Apartment Building in 1919, which still stands at Gough and Clay.

The Crothers house in 1919, later demolished. Vacant Holladay buildings visible in the background.

Developer Louis Lurie bought the remaining Holladay property in the 1920s, but eventually sold to the City and County of San Francisco in 1935. Except for the St. Regis building, the entire 4-block park was now owned by the City.

Lafayette Park more or less achieved its current design during the Great Depression, when the Recreation Department partnered with the federal Works Progress Administration to undertake significant public improvement projects throughout the city and fund jobs for tens of thousands of unemployed individuals.

All of the existing paths on the west side of the park were resurfaced, as was the children’s play area. New work in this section of the park consisted of converting the original convenience station into a utility shed, building a tennis court directly to the shed’s east, and constructing a new, larger convenience station to the east of the tennis courts.

On the eastern half of the park, the city merely maintained the areas it had owned since the nineteenth century. Holladay’s mansion and water tower were demolished; however, all of the pathways and stairs associated with the old estate were retained. The Crothers residence on Gough Street, just north of Clay, was also demolished (though this may have occurred earlier). WPA-funded work on Lafayette Park continued through 1942.

Work on the eastern side of the park, circa 1939

The WPA era park improvement plans

1948 aerial photograph showing completed improvements

Other than gaining a new playground and picnic tables in the early 1980s, Lafayette Park remained relatively unchanged until the renovations of 2012.

This 2010 survey shows the WPA additions in purple (bathroom, tennis courts). Blue areas were features associated with Holladay’s estate. Orange denotes features that existed by 1900.

2010 renovation plan

Lafayette Park Today

San Francisco citizens devoted over $10 million of the 2008 Clean and Safe Neighborhood Parks Bond to improving Lafayette Park. Design and planning began in 2010; construction was completed by 2013. Friends of Lafayette Park was instrumental in advocating for the community and realizing the park we enjoy today.

Sources

Alexander, Jeanne. “Lafayette Park History.” https://www.sfparksalliance.org/our-parks/parks/lafayette-park

Calisphere, http://www.calisphere.universityofcalifornia.edu

Carey & Co. Inc. Architecture, “Historic Resources Evaluation,” 2011. http://sfrecpark.org/DocumentCenter/View/1399/Historic-Resource-Evaluation-PDF

David Rumsey Historical Map Collection, http://www.davidrumsey.com

Holladay, Samuel Wirt. “Autobiography and Reminiscences of Samuel Wirt Holladay, San Francisco, 1901,” Society of California Pioneers. https://oac.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/kt258019dr/?brand=oac4

Kamiya, Gary. “How a Mime Troupe arrest sparked Bill Graham’s promoting career,” San Francisco Chronicle, Aug. 7, 2015.

King, John. “Lafayette Park revamp spurs heap of ideas,” San Francisco Chronicle, June 4, 2013.

Online Archive of California, https://oac.cdlib.org/

Open SF History, https://opensfhistory.org/

Pollock, Christopher. “At Home in Lafayette Square,” The New Fillmore. June 2, 2019.

San Francisco Recreation and Parks, Lafayette Park Renovation Project, http://sfrecpark.org/512/Lafayette-Park

Ready to pitch in?

Donate